Understanding this post requires reading Part I where I explain what reduced paths are and how we might go about proving they exist. In this second part, I’ll go into detail about how to use Zorn’s lemma to identifying a maximal cancellation and therefore ensure every path is path-homotopic to a reduced path. The argument we’ll use is a generalization of Cannon and Conner’s [3, Theorem 3.9], which is based on Curtis and Fort’s original argument in [4, Lemma 3.1]. Both of those papers restrict only to one-dimensional spaces and here we’re going to include lots of other spaces using a definition introduced in [2]. While writing this post, I’ve been surprised at how far the argument can be generalized.

We’ll use the same notation as in Part I: is a space,

is a non-constant path, and

is the partially ordered set of cancellations of

.

When can we be sure that pinching off null homotopic loops on a maximal cancellation results in a reduced loop?

At the start of Part I, I gave some examples of familiar spaces where some or all homotopy classes of loops failed to have any reduced representative. This means in order to continue this discussion, we must identify some hypothesis on that will allow us to move forward. The following definition has shown up in my work a good bit in the past two years. Curiously, it’s popping up again in a natural way. To distinguish notation, note that

denotes the fundamental group and

denotes the fundamental groupoid.

Definition 8: A space has well-defined transfinite

-products if for any closed set

containing

and paths

such that

and

for every component

of

, we have

.

This definition says that all infinite product operations (indexed by any countable linear order

) in the fundamental groupoid

are well-defined on homotopy classes: homotopic factors result in homotopic products. For instance, in the case that

, having well-defined transfinite products means that if we have path-homotopies

,

,

,… and we can form the infinite concatenations , then we have

(see the figure below). Why this is a hypothesis (and doesn’t just always happen for free) is because you may have no control over the size of the homotopies

and you need them to shrink in order to form a continuous homotopy on the product.

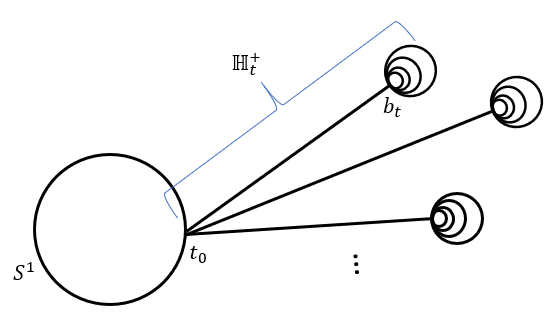

If the space has well-defined infinite products (a special case of transfinite products) then if the top (blue) paths can be deformed into the bottom (red) paths individually, then the entire top path can be homotoped to the entire bottom path.

The set in the definition could be the Cantor set, which means that we also need to consider the scenario in which the components of

are densely ordered. That’s the worst case scenario, which is still not so bad, since there can only be countably many components. Spaces with well-defined transfinite

-products abound, including one-dimensional spaces, planar sets, and lots of other spaces where “small null-homotopic loops are bounded by small disks.”

One remarkable thing about Definition 8 is that, for metrizable , this slightly-more-algebraic-flavored property is equivalent to

admitting a generalized universal covering space . I haven’t had a chance to write about those yet, but they’re expected to be the primary tool for understanding wild higher homotopy groups.

Lemma 9 (Construction of reduced paths): Suppose has transfinite

-products,

is a path,

is a maximal cancellation for a

and

. If

is the path induced by a collapse function

for

, i.e.

, then

is reduced and

.

Proof. Recall that since is maximal any two open intervals, which are elements of

must have disjoint closures. Let

so that

is the set of connected components of

. Let

be the path, defined as

on

and constant on each element of

(just like in the Pinching-off Lemma in Part I). If

, then

and

are both null-homotopic. So of course,

. Therefore, since

is assumed to have well-defined transfinite

-products, we have

. Now by Lemma 2 in Part I, we may find a collapse function

for

and a nowhere constant path

such that

. As pointed out in the comment after Lemma 2, we have

. Therefore,

.

Finally, we need to make sure that is reduced. Suppose to the contrary that there are

such that

is a null-homotopic loop. Find

such that

and

and

. Since

, it must be that

is a null-homotopic loop. But remember that

agrees with

on

and on any

that happens to lie in the interior of

,

is null-homotopic and

is constant. We once again apply the assumption that

has well-defined transfinite

-products to see that

. Hence,

is a null-homotopic loop. This allows us to define

. Let’s see why this gives us a contradiction.

If there was no contained in

or if there is some

such that

is a proper subset of

, then

is a strictly larger cancellation than

. This would violate the maximality of

. Because

, the only other possibility is that

. However this would mean that

is a point, contradicting the assumption that

. Either way, we run into a problem. So it must be that

is reduced.

Comment about understanding Lemma 9: Lemma 9 is packed with terminology from Part I so here’s how you can think about it. As long as has this well-defined products property, then given any maximal cancellation

, we can delete the subloops of

defined on the components of

(each of which is null-homotopic). I wrote the statement of Lemma 9 to avoid the case where

itself is a null-homotopic loop. In that case,

and

won’t exist and you can always represent with the constant loop anyway.

When do maximal cancellations exist?

Ok, so this is the last piece of the puzzle and this is the one that requires Zorn’s Lemma. What we’re trying to do is start with a path and show that the partially ordered set

of all cancellations of

has a maximal element. So this is ripe for an application of Zorn’s Lemma, which is equivalent to the Axiom of Choice. You shouldn’t really expect this to work without Zorn’s lemma because maximal cancellations are not unique and very much are like choosing a contraction of a tree.

One again, the well-definedness property from Definition 9 is the natural hypothesis to complete the proof.

Lemma 10 (Existence of Maximal Cancellations): Suppose has well-defined transfinite

-products and

is a non-constant path. Then there exists a maximal cancellation

for

.

Proof. Let be a linearly ordered subset of the partially ordered set

. The result will follow from Zorn’s Lemma, if we can show that

is bounded above in

. Let

. In otherwords, just union all of the open intervals together. Take

be the set of connected components of

. The main thing we’ll need to do is prove that

is a cancellation. However, once this is done it’s not too hard to see that

in

for all

.

The trickier part is showing that is a cancellation, i.e. that

is a null-homotopic loop for all

. Let’s fix such a connected component

of

. Notice that

. We need to pause and proof the following claim.

Claim: For every closed interval , there exists a

and

such that

.

Proof of Claim. Fix . For each

, we have

and so there exists

and

such that

. Now

is an open cover of the compact space

by open sets in

and so we may find a finite subcover

. Since

is a linear order,

exists. For

, we have

for some

and since

, we have

for some

. We must have

since

.

Equipped with this now-proven Claim, we’re really going places. Start with some . Find

such that and

. Using the Claim, for every

, we may find

and

such that

. This means that:

- Since each

is a cancellation,

is a null-homotopic loop!

Important early observation: Since the sequence converges to both

and

and we’ve assumed from the start that

is Hausdorff, it must be the case that

. All of the basepoints involved might be different but that’s ok… we’ll still work it out.

Define

Warning: It is possible that or

. In fact, we could have

and/or

for sufficiently large

. To make sure that this proof doesn’t require a bunch of tedious cases, we allow

to mean the constant loop at

when

.

Now, is homotopic to the

-indexed concatenation

. At worst, we’re inserting a sequence of constant subpaths and reparameterizing, which never changes the path-homotopy class.

Now we go back and use that third bullet point. First, is null-homotopic. Also, for

, we have

where

and

are null-homotopic loops. Hence

for all

.

Define to be the loop, which is defined as

on

,

on

and

on

.

Notice that is closed and and for every component latex

of

, we have

. Therefore, since

is assumed to have well-defined transfinite

-products, we have

. However,

is a reparemeterization of the path conjugate

of the null-homotopic loop

. Since

is a null-homotopic loop, it follows that

is null-homotopic.

Whew! Let’s put a little square here and be done with it.

An observation for those familiar with the Homotopically Hausdorff property: The well-defined transfinite products property is required when you run into densely ordered products. We really only needed products indexed by the naturals in the proof of Lemma 10. The subtleties of well-defined infinite path/loop products are studied in detail in [1] and are shown to be equivalent to the homotopically Hausdorff property when is first countable. So Lemma 10 could be strengthened as follows: Suppose

is first countable and homotopically Hausdorff and

is a non-constant path. Then there exists a maximal cancellation

for

.

Putting it all together

Finally, combining Lemmas 9 and 10, we finish off the existence of reduced paths.

Theorem 11: If has well-defined transfinite

-products, then every path in

is path-homotopic to a reduced path induced by deleting subloops on a maximal cancellation.

Proof. If is a null-homotopic loop, then the constant loop is the desired reduced representative. Otherwise,

is a non-constant path. Lemma 10 ensures that

contains a maximal cancellation

. Lemma 9 ensures that if

and

is the path induced by a collapse function

for

(these details were laid out in Part I), then

is reduced and

.

What else is there to wonder about?

To what extent are reduced representatives of paths unique? In general, there is definitely no uniqueness within homotopy classes – recall the cylinder example from Part I. Even relative to the subloop deletion construction, the result won’t be unique. For suppose that are reduced paths that are path-homotopic to each other. Then

, reduces to

using the cancellation

or

using the cancellation

. There is choice involved! That choice will typically result in one of many possible reduced path results. This shouldn’t be too surprising though. It’s a slightly more topological version of the fact that in a group that is not free, shortest representation of an element using finite products of generators may not be unique.

However, I hinted in Part I that for one-dimensional spaces that every path-homotopy class has a unique (up to reparameterization) reduced path – I love this result. Maybe a Part III?

References:

[1] J. Brazas, Scattered products in fundamental groupoids. Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 148 (2020), no 6, 2655-2670. arXiv

[2] J. Brazas, H. Fischer, Test map characterizations of local properties of fundamental groups. Journal of Topology and Analysis. 12 (2020) 37-85. arXiv

[3] J.W. Cannon, G.R. Conner, On the fundamental groups of one-dimensional spaces, Topology Appl. 153 (2006) 2648–2672.

[4] M.L. Curtis, M.K. Fort, Jr., The fundamental group of one-dimensional spaces, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 10 (1959) 140–148.