Recently, I ran into a situation where I had an inverse sequence of *planar Peano continua. I wondered naively if the limit of such a sequence always had to be planar. It turns out the answer is no, even in the one-dimensional case, but I don’t this fact is particularly obvious. After a literature search I found a really nice example that I can’t help but share.

*A Peano continuum is a connected, locally connected, metrizable space (equivalently, a continuous image of ) and a space

is planar if there exists a topological embedding

. For instance, the Sierpinski Carpet is a planar Peano continuum.

Kuratowski’s Theorem [3] says that a connected graph is planar if and only if it contains a topological copy of

or

(see below).

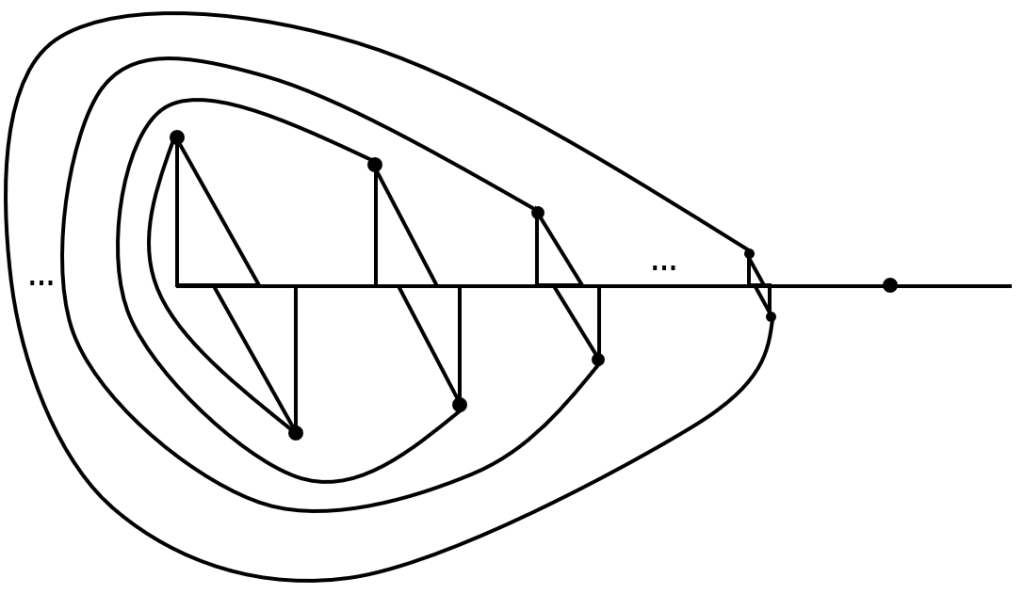

Let’s use an infinite null-sequence of copies of but without the large overarching arc. We’re going to connect these and make them limit to a point. We’ll also extend the connecting line a little past the limit point. We end up with the following space

. Kuratowski actually mentioned this space in [5] and suggested it’s potential importance.

Let’s see why is not planar. Let’s call the long diagonal edges in the each partial copy of

the “crossing edges” since these are involved in a crossing-over. The sequence of crossing edges is null in the sense that the diameter of these edges approaches

. We could take finitely many crossing edges and push them over the left end. But we can’t move all of them over the left end or we wind up with a space that is not homeomorphic to

. Similarly, because we have extended the connecting line a little past the limit point on the right, we can only push finitely many of the connecting edges over the right side of the space. Hence, any embedding into

would have infinitely many crossings somewhere and we’d have a contradiction.

However, if we delete all but finitely many of the partial copies of , we would end up with a finite planar graph:

This finite approximation graph is planar since there are only finitely many crossing edges and we can move all of them over the left side. Here’s a planar embedding of this finite approximation.

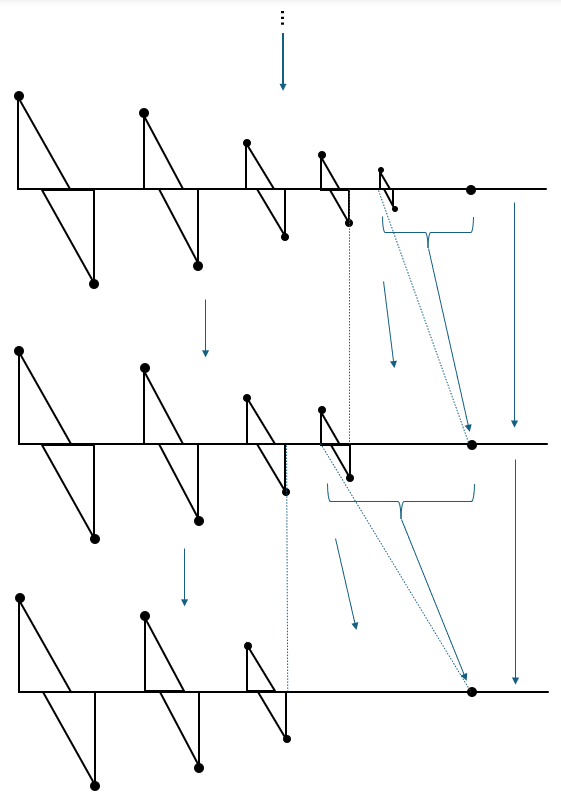

These finite approximations (where we keep only finitely many partial copies of can be put into an inverse system whose limit is homeomorphic to

. To do this correctly, you need to define the bonding maps carefully. Let

be the finite graph consisting of the entire horizontal arc and

of the partial copies of

, let’s call them

. To ensure that the subspaces

shrinking toward the limit point on the arc as

, we need to define the bonding map

to map

and the arc connecting

to the limit point to the limit point. We map

to itself by the identity for all

, including the arcs connecting them. The arc connecting

and

we stretch out and map onto the arc connecting

and the limit point in

. I’ve illustrated the maps

and

below.

It’s not too hard to see that . Hence, we have the following answer to my original naive question: The inverse limit of one-dimensional planar Peano continua need not be planar.

You can also perform a similar construction with . In particular, the following space, which we’ll call

is built out of partial copies of

in an analogous way.

I learned about these spaces in the paper [1]. It also taught me about the following remarkable statement proved by S. Claytor in 1937.

Claytor’s Theorem [2]: A Peano continuum embeds in if and only it does not contain a homeomorphic copy of

, or

.

This completely characterizes the planarity of Peano continua in a way that directly extends Kuratowski’s Theorem! Amazing!

References

[1] R. Ayala; M. Chávez; A. Quintero, On the planarity of Peano generalized continua: An extension of a theorem of S. Claytor, Colloquium Mathematicae 75 (1998) no. 2, 175-181.

[2] S. Claytor, Peanian continua not imbeddable in a spherical surface, Ann. of Math. 38 (1937), 631–646.

[3] K. Kuratowski, Sur le probl`eme des courbes gauches en topologie, Fund. Math. 15 (1930), 271–283.