This is the last in a sequence of posts about the quotient topology. This one is about how the topological structure of can be used to classify certain generalizations of covering maps for locally complicated spaces. Sometimes it still amazes me how this works out. For a sneak peak, see the table at the end of the post.

Ordinary covering maps

One of the things we love about covering space theory is that covering spaces over a locally nice (path-connected, locally path connected, and semilocally simply connected) space are completely classified by the subgroups of

. In particular, for every subgroup

, there is a based covering map

such that

. Moreover,

is unique up to based homeomorphism for given

and the covering space can be built using a “standard construction.” In particular, if

is the trivial subgroup, then

is simply connected and we call

a universal covering map.

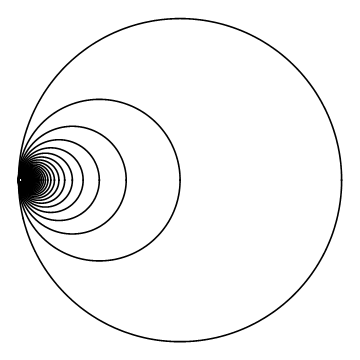

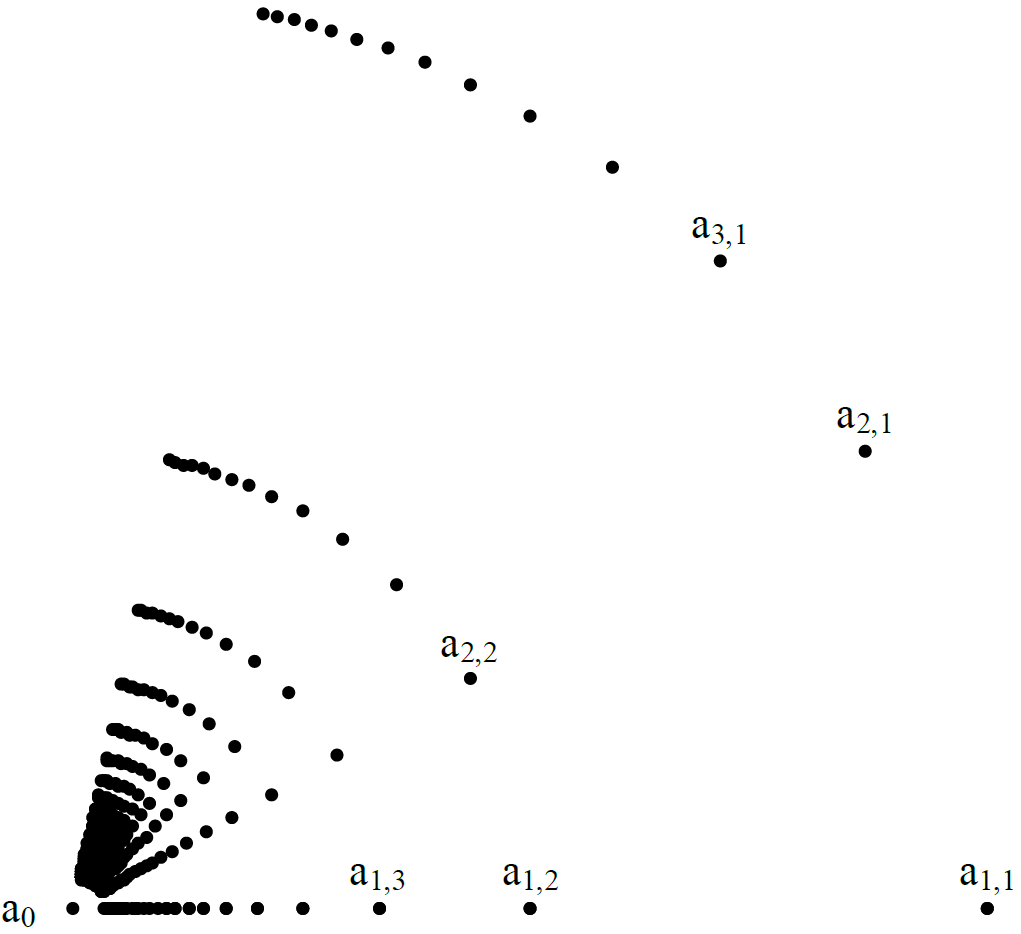

Now, let’s say we drop the semilocally simply connectedness assumption. So is still path-connected and locally path connected but it’s not semilocally simply connected so there is some point in

where arbitrarily small loops are not be null-homotopic. In this case,

won’t have a simply connected covering space. In extreme cases like the harmonic archipelago or Griffith twin cone, the only covering map over

will be the identity map. However, in general,

is likely to still have lots of non-trivial covering spaces. Standard arguments still show that if

and

are based covering maps that both correspond to the same subgroup

under the usual correspondence. That is, if

for

, then there is a based homeomorphism

such that

. Yep, go back and check your algebraic topology textbook. The “semilocally simply connectedness” condition is only needed for the existence of covering spaces. It has nothing to do with uniqueness up to homeomorphism. Now…if you thow out the locally path-connected condition, then you could start getting into trouble. But let’s not go down that path.

Uniqueness still working out means that the covering spaces over are still classified by the subgroups of

it’s just that not ALL subgroups of

correspond to covering spaces. So maybe there is something special about these particular subgroups of

that do happen to admit a corresponding covering map. It sure would be cool if they are classified by a topological property related to

. But what could it be? Does a subgroup

correspond to a covering map if and only if

is open in

? Or closed? Or some other topological property a subgroup might have?

It turns out that there is such a classification. However, we need a definition.

Deifnition: The core of a subgroup of

is the largest normal subgroup of

contained in

. You can define this explicitly as

.

Apprently this construction is important in finite group theory.

Theorem: Suppose is path connected and locally path connected. A subgroup

admits a based covering map

with

if and only if

has an open core in

. Moreover, there is a canonical Galois correspondence:

{Equiv. classes of based coverings over }

{subgroups of

with open core}.

Semicovering maps

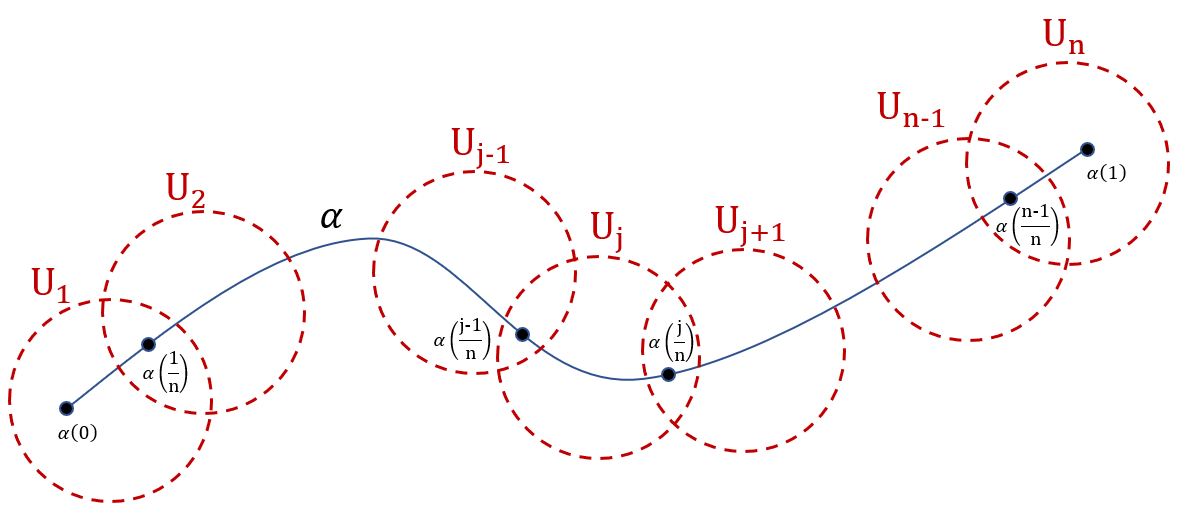

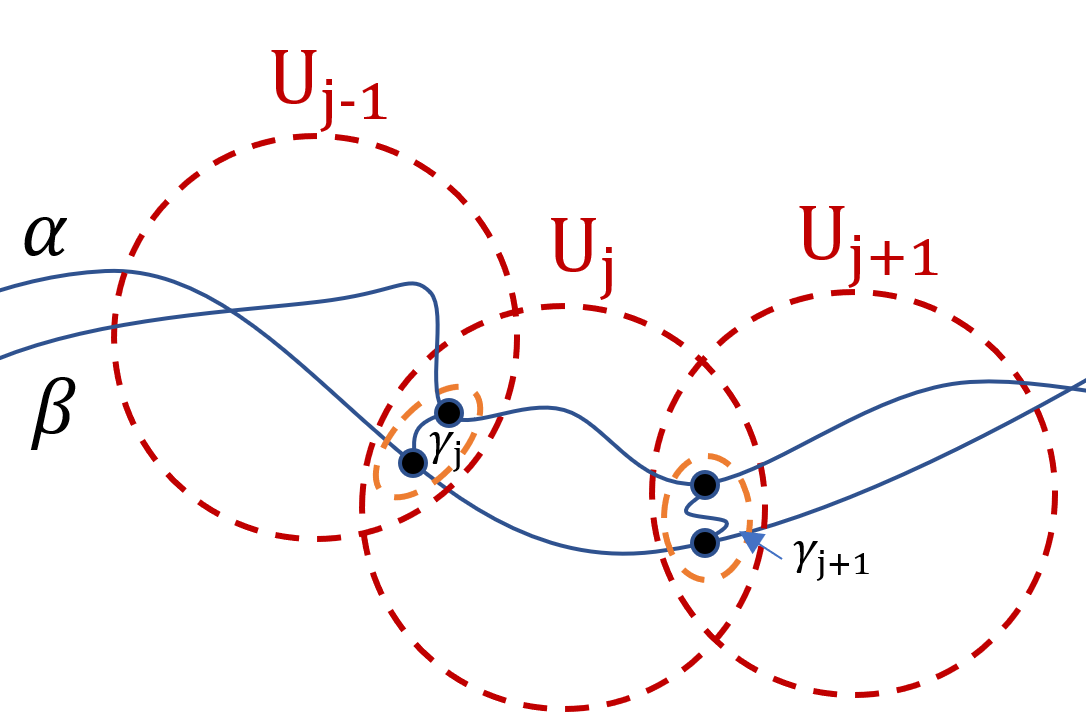

A while back, I wrote a couple of posts about semicovering maps. This is a weak version of covering map so every covering map is a semicovering map. The two notions agree on “locally nice spaces” but start to pick out intricacies for non semilocally simply connected spaces. It turns out that semicoverings are classified by the open subgroups of . I realized this when I was working on my thesis after defining semicoverings and, honestly, I was totally shocked!

Theorem: Suppose is path connected and locally path connected. A subgroup

admits a based semicovering map

with

if and only if

is open in

. Moreover, there is a canonical Galois correspondence:

{Equiv. classes of based semicoverings over }

{open subgroups of

}.

Continuous path-lifting maps

After seeing the classification of covering maps and semicovering maps for locally path-connected spaces, you might say well… what about other properties of subgroups? Do they correspond to some special class of generalized covering maps. I’d say, that this does often have a positve answer but there are some limitations. For instance, every closed subgroup of does admit a Serre fibration with totally path-disconnected (t.p.d.) fibers that corresponds to it. However, not all such maps come from closed subgroups – the class of Serre fibrations with t.p.d. fibers is super useful but is too big for this classification and it’s not known exactly what is topologically special about the Serre fibrations that do correspond from closed subgroups. This is a good problem.

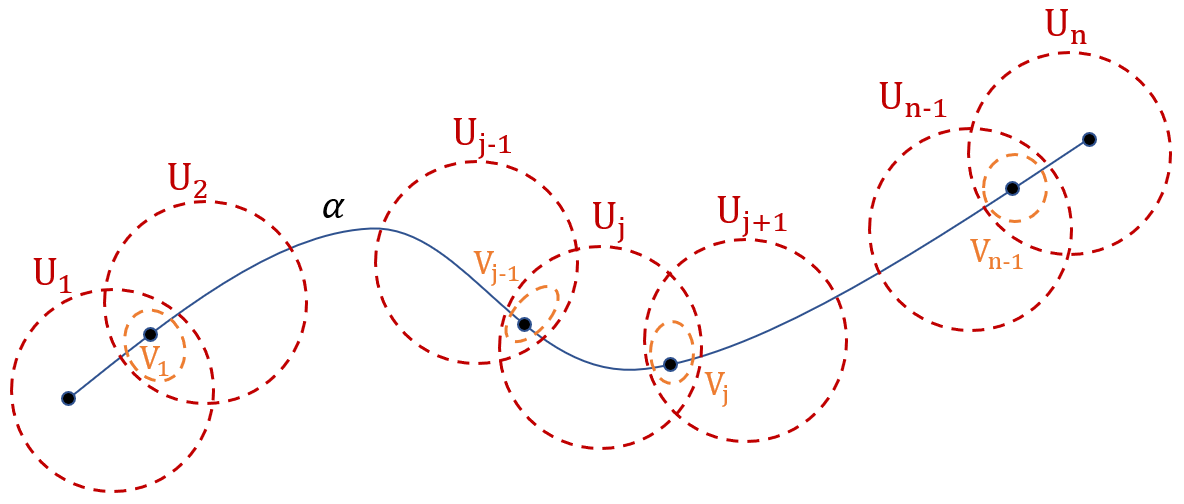

However, here’s another example. For a based space , let

be the space of paths in

starting at

with the compact-open topology. A map

has continuous path-lifting (we’ll call it a CPL-map) if for each

, the induced map

,

is a homeomorphism. That is,

uniquely lifts paths and if a sequence or net of paths (starting at the same point) converges downstairs, then the lifts upstairs also converge. These maps classify subgroups

with a totally path-disconnected coset space!

Theorem: Suppose is path connected and locally path connected. A subgroup

admits a based CPL-map

with

if and only if the coset space

is totally path-disconnected. Moreover, there is a canonical Galois correspondence:

{weak equiv. classes of based CPL-maps over }

{subgroups

with

tot. path-disc.}.

Note that a certain notion of “weak” equivalence classes needs to be used here but this is pretty superficial. Instead of using homeomorphisms, you use bijective weak homotopy equivalences…so it’s still pretty rigid. This becomes equivalence up to homeomorphism if you restrict to a certain category. See https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.03667 for more details.

Here’s a table summarizing the classifications that are known and a couple that are relevant but not fully understood

In the table, classes of based maps over a given space appear in the left column. Next to each one in the middle column is the topological property a subgroup may or may not have with respect to the quotient topology on the fundamental group. The subgroups having that property completely classify the type of maps in the left column.

| Type of Map | Property of classifying subgroup H in |

Classificaiton up to equivalence? |

| Covering map | H has open core | Yes |

| Semicovering map | H is open | Yes |

| Inverse limit of covering maps | H is an intersection of open normal subgroups | Yes |

| Inverse limit of semicovering maps | H is an intersection of open subgroups | Yes |

| CPL (continuous path-lifting) map | Yes*, in a certain category | |

| Hurewicz fibrations with unique path lifting | ? | ? |

| (mystery class ?? of Serre fibrations with unique path lifting) | H is closed | ? |

What’s your favorite property a subgroup might have? Assuming it at least implies “closed,” we could ask what kind of generalized covering maps correspond to subgroups with that property.